SF homeless tents reach lowest level since 2019

PLUS: The first 100 Days of Mayor Daniel Lurie

What You Need To Know

Here’s what happened around the city for the week of April 13, 2025:

- SF homeless tents reach lowest level since 2019

- The first 100 Days of Mayor Daniel Lurie

- Mayor Lurie Orders Deeper Budget Cuts Amid Federal Funding Threat

- Supervisor Fielder wants to extend homeless shelter stays

Recent & upcoming openings:

- Kolapasi serves us South Indian in the Mission

Research

- How San Francisco built a Homeless System that Fails its Most Vulnerable

SF homeless tents reach lowest level since 2019

Published April 14, 2025

The number of tents on San Francisco streets continues to decline, with a 62% drop since this time last year, and an 80% drop since the COVID peak. It's the lowest level the city has recorded since records began in 2018.

The Facts

San Francisco counted just 222 tents citywide in April 2025, a 62% decline from the same time last year, marking the lowest number since city officials began tracking in 2018. Notably, tents in the Mission District fell dramatically from 92 to only 9, according to the Chronicle.

Image credit: SF Chronicle

The Context

The decline in tents began under former Mayor London Breed, and has continued under Mayor Lurie. The Lurie administration has enlisted the help of the Department of Emergency Management, rather than rely on SFPD or homeless nonprofits, to address the issue. This approach appears to be working, with the mobile triage unit at 6th Street seeing over 12,000 visits in the first month of operations.

The reduction is attributed to increased enforcement—including arrests and citations—and the opening of additional shelter beds.

The GrowSF Take

This progress shows that targeted, consistent enforcement paired with expanded shelter capacity makes a real difference. The Lurie administration should continue in its effort to stand up new shelters, and ensure that the highest need people get specialized care.

The first 100 Days of Mayor Daniel Lurie

Published April 16, 2025

100 days into Mayor Daniel Lurie’s first term, San Francisco is cleaner, safer, and more hopeful. Crime is at a 23-year low, tents are disappearing, and businesses are reinvesting in the city.

The Facts

In first 100 days of the Lurie administration, crime in San Francisco has fallen to its lowest level in 23 years — with car break-ins down 41%, property crime down 35%, and violent crime down 15% compared to last year. Homeless tents are at their lowest point since tracking began, dropping 92% in the Mission and 67% in SoMa. Meanwhile, Muni ridership is up to 75% of pre-pandemic levels, and hotel occupancy is rising.

The Context

Mayor Lurie took office amid a $1 billion budget deficit, a fentanyl overdose crisis, a sluggish downtown recovery, and rising public frustration. The latest available polling shows that, for the first time in over five years, more San Franciscans think the city is heading the right direction than on the wrong track.

The GrowSF Take

City Hall doesn’t have to be slow, bloated, or ineffective. Crime is down, tourism is up, tents are disappearing, and businesses are returning.

It’s not magic — it’s focus, urgency, and the political will to make things better. There’s still a long way to go, but if the next 100 days look like the first 100, San Francisco has a real shot at becoming the city we all know it can be.

Mayor Lurie Orders Deeper Budget Cuts Amid Federal Funding Threat

Published April 17, 2025

Mayor Daniel Lurie has directed city departments to identify additional budget cuts to address an $818 million two-year deficit and prepare for a larger deficit due to cuts in federal funding.

The Facts

Mayor Lurie has instructed city departments to find further budget cuts beyond the previously requested 15% reductions, which many departments did not fully implement.

Departments are required to submit detailed information about their federal funding sources, grant-funded programs, and professional service contracts by April 25, with a budget proposal due by June 1.

The Context

The city faces an $818 million two-year budget shortfall, which could rise to nearly $2B after federal funding cuts proposed by the Trump administration. These extra cuts would impact "public safety, housing, healthcare, food benefits, and environmental projects," according to the Chronicle.

San Francisco's financial challenges are compounded by a sluggish economic recovery, with downtown areas experiencing reduced tax revenues due to vacant offices and storefronts. The potential for significant federal funding cuts under the Trump administration adds to the city's fiscal uncertainty. Mayor Lurie has emphasized the need for structural, long-term solutions rather than temporary fixes to address the ongoing budget deficits.

The GrowSF Take

Mayor Lurie's proactive approach to addressing San Francisco's budget crisis is a necessary step toward fiscal responsibility. By demanding deeper budget cuts and preparing for potential federal funding reductions, the city acknowledges the structural nature of its financial challenges. This situation underscores the importance of efficient governance and the need to prioritize essential services while eliminating wasteful spending. GrowSF supports efforts to streamline city operations and ensure that taxpayer dollars are used effectively to maintain critical services for all residents.

Supervisor Fielder wants to extend homeless shelter stays

Published April 15, 2025

San Francisco's homeless shelters are intended for short-term stays, and are capped at 3 months with optional extensions as necessary. Shelters help people stabilize, get back on their feet, find help from family and friends, or get triaged into higher-need programs. But Supervisor Jackie Fielder wants to let people stay in temporary shelter for up to one year.

The Facts

In December 2024, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing reinstated the 90-day stay limit for families in shelter, with optional 30-day extensions. This is the same policy that existed before COVID, but it was temporarily suspended for the pandemic.

Supervisor Jackie Fielder is introducing legislation to change this limit to 365 days, with the option to stay longer if needed.

The Context

The 90-day rule was created to speed up the transition to permanent housing and ensure shelter beds remain available for new families. During COVID, when the limit was temporarily suspended, people were stuck on the street for longer periods of time, and the city saw a rise in encampments. The 90-day stay limit ensures that people who have just become homeless get a chance at getting back on their feet, while also allowing the city to triage people into higher-need programs.

The GrowSF Take

This isn’t a simple case of “let people stay longer.” We agree the system should never force families back onto the street — especially children — but ending time limits without adding shelter capacity will only make things worse.

People who have recently become homeless have greater success in finding permanent housing when they are quickly helped, rather than letting them languish on the streets until a shelter bed becomes available at some indeterminate time in the future. When the city can predict when beds will become available, it can help people better.

Of course, this means the city needs to continue to build more shelter capacity, implement more programs to help the highest need people, build more low-income housing, and boost market rate housing production which generates the taxes that fund these programs. The city has made some progress, but it’s not enough.

Love the GrowSF Report? Share it

Help GrowSF grow! Share our newsletter with your friends. The bigger we are, the better San Francisco will be.

Recent & upcoming openings

A great city is constantly changing and growing, let’s celebrate what’s new!

Kolapasi serves up South Indian in the Mission

WHERE: 3465 19th St

It’s not exactly recent, but your editor did eat there recently :)

Kolapasi opened in the Mission in late 2024 and we’re sorry to say we missed it! They have joined a growing chorus of new Indian restaurants popping up in the Mission. I went Thursday night, and it was packed at 9pm. Try the Alapi fish curry, gongurra chicken biryani, and the Bagara Baigan (eggplant)!

Research

How San Francisco built a Homeless System that Fails its Most Vulnerable

Published April 13, 2025

San Francisco’s approach to homelessness is called “housing first.” This sounds great, but it only serves about one third to one half of homeless people well. Many people need psychiatric care, many others need drug and alcohol treatment, and some need full-time supervision. Our system fails these people, and rather than end up indoors they bounce between a tent and the emergency room. Here’s how we got here.

In 2002, a legislative analyst report requested by Gavin Newsom, who was then the District 2 Supervisor, found that San Francisco’s Cash Assistance programs were the highest maximum cash grants in the state (both overall, and per-capita) – and that rather than giving out cash, other Bay Area counties had chosen to provide in-kind services like shelter, clothing, and food. The analysis found that just about every other county switched from providing cash assistance to in-kind services in order to save costs, and that this policy change occurred between 1990 and 1996. The report does not mince words. “We should adopt in-kind services over cash assistance,” it concluded on May 9, 2002.

This 2002 legislative report was the driving force behind Proposition N “Care Not Cash”, sponsored by Gavin Newsom in 2002, and passed by voters the same year. Care Not Cash changed San Francisco’s General Assistance from $395 per month to just $59 per month but came with a guarantee of housing and food for the homeless. The measure stated that if the services weren’t available, the city could not reduce a homeless person’s aid. The idea being: the city’s savings from no longer spending on welfare checks (an estimated $13M in savings at the time) would create more affordable housing, expand shelters, and add treatment beds.

Gavin Newsom’s Care Not Cash legislation marked the beginning of a sea change in San Francisco’s approach to homelessness. It was the first domino to fall that culminated in a 10 year homelessness strategy titled the “Plan to Abolish Chronic Homelessness” – the cornerstone of this plan was above all to provide housing for the homeless, which became known as Housing First.

The New 2004 Plan: “Housing First”

San Francisco’s homelessness policy from the mid 1980s until 2004 was the “Continuum of Care” model, which was made up of three main efforts:

Prevention through eviction defense, emergency grants, and education.

Outreach to all people facing homelessness.

Supportive services including substance abuse treatment, job, training, housing placement, and child care (among many such services).

It was basically a smorgasbord of many different services, outreach programs, and city department efforts.

The 2004 Plan To Abolish Chronic Homelessness set a 10-year plan to end the Continuum of Care approach and move to a Housing First model, committing the majority of our budget and resources to building permanent supportive housing.

As the report describes in its own words, permanent supportive housing was supposed to be more effective, affordable, and humane approach to addressing homelessness:

“The model of housing with on-site supportive services has proven to be most effective in housing persons who have been homeless and struggling with mental illness, substance abuse, and other issues. It is clearly more humane and cost effective to provide someone a decent supportive housing unit rather than to allow them to remain on the street, and/or ricochet through a high cost setting such as the jail system or hospital emergency rooms. Such institutions offer incarceration or treatment, but are no more than expensive revolving doors leading back to the streets.”

- The San Francisco Plan to Abolish Chronic Homelessness, Page 25

Measuring outcomes

It has now been over two decades since San Francisco adopted the Housing First model. And the first lines of the 2004 strategy still sound eerily similar to the headlines of today: “San Francisco is Everyone's Favorite City. But San Francisco also has the dubious distinction of being the homeless capital of the United States.”

To consider the outcomes of the Housing First model, we draw our evidence from one of SF’s most comprehensive policy reports which tracked 1,818 people who were homeless over eight years, from 2007 until 2015. Specifically, the report tracked adults as they entered and moved through San Francisco’s Housing First programs.

Note: Data on the effectiveness of San Francisco’s Housing First efforts gets more complicated to decipher after mid-2016 when the Department of Housing and Homelessness was created, due to a complete reorganization of funding, outcomes tracking, and policy research. We hope to follow up this report with more analysis of the recent data.

Our city’s Housing First model has had three major implications:

1. The Vast Majority of Homelessness Costs come from Emergency Room / Urgent Care: 57% of all costs from 2007-2015

Between 2007 and 2015, the majority of money spent on homelessness in San Francisco went towards emergency and urgent care, including emergency department visits, psychiatric emergencies visits, and ambulance transports. Across all 1,818 people that the policy report tracked, emergency/urgent care costs accounted for 57% of total costs. The actual cost of the supportive housing was negligible compared to the service costs that included emergency care.

While there has not been a report as comprehensive as this one since 2015, documentation of the ongoing cost burden of emergency care continues. For instance, a 2019 Fire Commission meeting noted that over 40% of San Francisco’s homeless population use the city’s ambulance service. And moreover, that there were outstanding costs of at least $50M that the Department of Homelessness should pay.

A 2023 hearing from the SFFD confirmed that this trend has continued, noting that 25% of all ambulance trips involve people who are homeless. And over a five-year period, 5 chronically homeless individuals took over 1,800 ambulance trips, costing the city $4M in transportation costs alone. The sad reality is that despite the amount of trips they took to the hospital, their outcomes were not notably better: two of them died, two remain in shelter, and one remains in mental health conservatorship.

2. The Greatest Costs come from an Extremely High-Need Minority: 16 people cost SF almost $1M each

Before going into supportive housing, just 162 adults, 9% of the total homeless population, cost $113.6M over 8 years, accounting for 42% of total service spending. 81% of that ($92.3M) was spent on emergency/urgent care costs. In their most expensive years, each of these adults cost the city $182,428 due to emergency room visits.

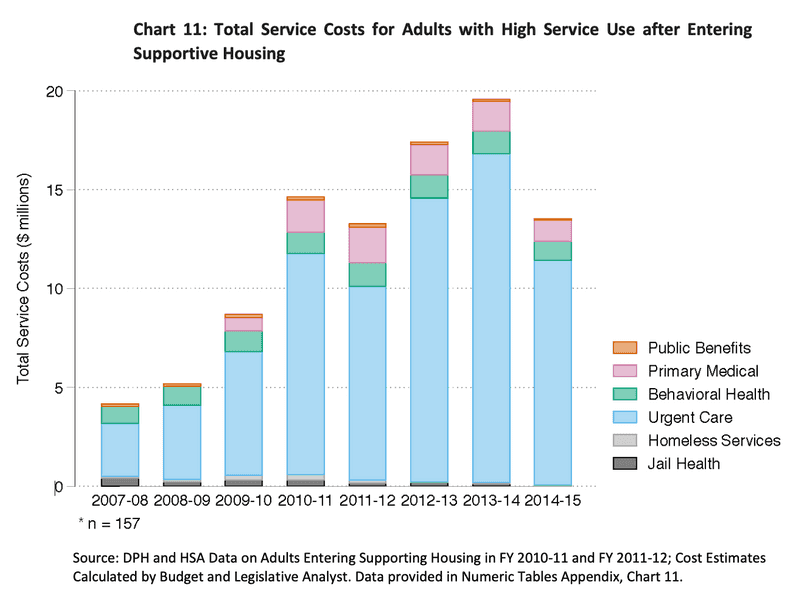

After entering supportive housing, however, the outcomes were just as bad. 157 adults made up for the top 10% of service users by cost, and 79% of all spending on this group was on emergency/urgent care. And importantly, spending on services increased 352% during their time in supportive housing – the vast majority of which was spent on urgent/emergency care. However, some of that increase is due to general cost inflation which affected all groups, according to the report.

Across the high service users, 58 people were consistent across both groups (before entering supportive housing and after). These 58 adults cost $54.4M in services. Of these 58 adults, 16 of them died after placement in supportive housing. These 16 adults comprised 28% of the overall spending on services for the group of 58 adults, making up $15.1M of the $54.4M spent.

That’s almost $1M per person.

3. Our Emphasis on Housing First has Distracted us from More Humane and Cost-Effective Solutions For Those Who Need the Most Help

Placing the highest need people into a Mental Health Rehabilitation Center (MHRC), which offers 24/7 intensive psychiatric care, nursing care, and psychosocial rehabilitation services to adults with severe mental illness and/or placed under conservatorship is more humane and cost-effective than letting people languish in supportive housing with emergency room visits.

24/7 care would result in fewer ER visits, better health, better quality of life, and less trauma on the street. And it would save taxpayers 20% - $41M instead of $54M.

The average length of stay at a Mental Health Rehabilitation Center in San Francisco is 2.2 years. So at $527 per day, that’s $24.5M for 58 people. After that, these people can go to a lower-intervention center, but still be cared for. If they were to move to an Adult Residential Facility which provides basic care and supervision, that would cost $200 a day. For 58 people, that’s $16.9M for 4 years. Meaning 6 years would cost a total of $41.4M and likely result in fewer deaths and more humane outcomes. That’s $10M less than the revolving door of supportive housing and emergency room visits, but importantly, it would likely be a more humane path for those who need the greatest help.

Current Housing-First Model ($54.4M)Treatment-First Model ($41.4M)Fast-tracked into Supportive HousingPlaced in a Mental Health Rehabilitation Center for 2 years ($24.5M)Remains in Supportive Housing with constant emergency room visitsPlaced in an Adult Residential Facility for 4 years ($16.9M)

For the people who need more dedicated medical care, Housing First seems callous: it is a way of concealing the problem by shepherding those who cannot take care of themselves into private rooms out of the public eye.

Housing First is not the right solution for untreated mental illness or drug addiction. Placing those who need medical attention in supportive housing is nothing more than hiding the problem. Those who need medical care, as the evidence shows, will continue to revolve in and out of emergency rooms rather than getting the sustained care that they need.

To implement this better approach, though, we must first expand the facilities that provide these services. San Francisco has a shortage of mental health treatment beds, but building more will save us money and keep more people alive.